Asian men are represented in one of two ways: either as the wimpy egghead or the kung fu master/ninja/samurai. “He is sometimes dangerous, sometimes friendly, but almost always characterized by a desexualized Zen asceticism,” says Richard Fung, artist and post-colonial theorist.

Soft-spoken and shy, the nerdy Asian coworker or classmate may be hardworking and successful, but he rarely exudes sexuality. Today, when everything between French fries and surveillance database boast a vigorous bigger-is-better gusto, every Asian guy who has ever suffered a “small penis” joke knows the unsettling feeling of being emasculated by a culture in which the words “beautiful”, “handsome”, and “sexy” wear a white face.

This article discusses the ways Asian men are stripped of their masculinity and have their sexuality feminized, and postulates that East Asian popular music culture (i.e., Korean pop music) may be a harbinger for reappropriating the “feminine” aesthetic.

Due to the Western conception of “the Orient” in the 19th-century as foreign and exotic, a land and people to be observed and colonized, East Asian culture has been represented as alluring, passive, and feminine.Just as the exploration of the American West constructed an egocentric and masculine cultural identity for the frontier, so too did the penetration of new Asian markets for enticing and unfamiliar goods such as tea, silk, and porcelain.

For Asian people, the result of gendered projections onto their cultural identity has been the fetishization of Asian women and the desexualization of Asian men. Asian men seeking employment in the United States in the 19th-century were relegated to launderers, tailors, cleaners, and cooks: “women’s work.” U.S. laws prohibiting Asians from marrying whites persisted through the 1960s until the repeal of all anti-miscegenation laws in 1967 with Loving v. Virginia. While Asian women, allied with second-wave feminism, have begun dialogue about the oppressiveness of “yellow fever” in the eroticized “geisha girl” and “China doll” tropes, Asian men have remained notably silent.

Mainstream narratives of Asian men as viable and attractive romantic partners often rely on gendered stereotypes and “Otherization”. In a Newsweek article “Why Asian guys are on a roll” by Esther Pan, Asian men are described as “something different,” and a “smart, genuine, respectful” alternative to the “all-American guy.”If the Asian man is “different” and therefore opposite to the “all-American” guy, his gendered traits are also opposite to the normal, “masculine” image of the white male.

Shortly after, The Seattle Times published David Nakamura’s satirical piece, “They’re hot they’re sexy… they’re Asian men”, in which the author revealed longstanding stereotypes confronting Asian-American men. They were described by white women as “the best-kept secret around,” having a “slender physique,” “beautiful eyes,” and a “combination of ‘old-fashioned’ values and New Age insights that many women desire.” If wanted at all, Asian men are desired for traditionally feminine traits or their exotic, perceived New Age-spiritual identity. Romantically labeled as “different”, Asian-American men are set outside the ideals of the “normal”, “all-American” concept of masculinity.

The Asian male feminization have some peculiar social effects. Asian guys tend to either date “alternative types”, e.g., nerds, hipsters, or Asian girls, facing barriers in mainstream attraction (upon discovering that the pop star Lorde had an Asian boyfriend, the internet had a racist meltdown).

In the gay community, gay Asian males are expected to be submissive, and are “desirable only for a select subgroup of men who favor ‘femmes’ over ‘real’ men”. Eurocentric standards of attraction and the invisibility of Asian men in gay publications reduce the self-confidence of gay Asians and determine the overwhelming preference of white sexual partners. In the world of drag queens, Asian men are perceived as possessing a “natural advantage” over their white competitors due their ability to “pass” as real women and be more “authentically” feminine. Yet, given the historical and cultural context outlined above, are Asian-American men more successful because of their “delicate features,” or because the white judges and conditioned audience cannot see them as anything but feminized?

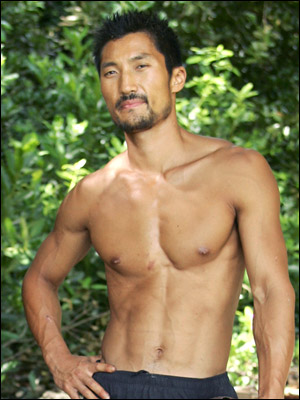

A lack of positive and mainstream representation in television and movies of Asian men lies at the heart of the problem. While academics write about the emasculation of Asian-American men, the publicity of the issue is as prevalent as Asian representatives in Hollywood (that is, little). Perhaps the most notable individual who has spoken out about Asian male stereotypes is Yul Kwon – (who?) – the winner of Survivor: Fiji.

Yul Kwon, admired for what’s inside his head as much as what’s underneath his shirt: Kwon was a strategic player in a season intentionally split along ethnicities by the show’s producers.

In lieu of mainstream role models, Asians have taken to the democratic platform of YouTube, and KevJumba, Timothy DeLaGhetto, and Wong Fu Productions have made videos on thecommon theme of girls, interracial relationships, and self-image, in order to challenge stereotypes and encourage individuals to have pride in themselves and their identity. With their massive following, these individuals are vital oases to many Asian-Americans in the desert of popular culture’s stereotypical Asian representations.

However, there are changes on the (Eastern) horizon: in Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, male beauty norms have undergone a transformation from the tough machismo of soldiers and gangsters to the effeminate beauty icons of Korean pop stars, or kkonminam (kkot = flower; minam = handsome man). Before asking if such a change could happen in the U.S., one first asks: Why? What could cause the disruption of masculinity, a strong foundation to these patriarchal cultures?

The answer: K-pop.

Since the late 1990s, Korean pop music has extended its reach throughout Asian and into the West, trumpeting a stylish, sleek aesthetic that combines cool R&B dance moves and catchy hooks. It’s taking over the world, breaking national boundaries and prejudices.

Some commentators associate the rise of kkonminam to the surge of popularity in Korea of the female-oriented yaoi comic genre, which originates in Japan. (The male characters in yaoi are usually drawn as androgynous and engage in homoerotic or homoromantic relationships; while targeted to young women, it is read by both males and females.) Others attribute the growth of male beauty to the changing role of men in society: in both the United States (remember how “metrosexual” entered the vocabulary?) and Asia, the popularity of the violent and brutish representations of masculinity is fading.

While these factors underlie the smooth faces and plucked eyebrows of the new, feminine Asian man, it’s still lady’s choice. If young women, the primary consumers of these forms of media, find slim and stylish men desirable, then these men, with their pretty faces, are the prototypes to a new standard of attractiveness.

The danger of K-pop looks and the kkonminam aesthetic is that, if universalized, they have the potential to reduce young men into commodified or fetishized bodies. On the other hand, efflorescent gender presentation and fashion allow individuals to embrace and rewrite their experience as desexualized or feminine men.

Studying the use of unconventional, feminine dress codes in Taiwanese men, Shiau and Chen write that “the employment of feminine aesthetics and strategies has enabled us to refute silently imposed ideological assignments and cultural expectations to reproduce the conventional masculine order in the post-capitalist Taiwanese society.” These “new Taiwanese men,” wearing Calvin Klein suits and Armani shoes, enjoy the experience of being “gazed at and wanted” like male models: clean and crisp, sexual and submissive.

In a postmodern, transnational economy, commodities and culture alike become global – “Gangnam Style” proved that much. If Taiwanese men utilize Western fashion to connote a new sexuality, can Asian-American men leverage K-pop as a cross-cultural catalyst to reappropriate their ascribed femininity?

Potentially. The warm reception of Korean icons into American culture creates a space for “alternative” masculinities to become independent of their necessary opposition to the “all-American” masculinity. For Asian-American men, to see familiar body types and facial features in famous entertainment personalities is affirming. If K-pop continues to receive popular acclaim, Asian-Americans may be seen as more attractive and sexualized.

However, it is certainly not the sole answer to the variegated problem of racialized sexuality. Many individuals under the umbrella term “Asian-Americans” do not identify with the music and celebrities so heavily associated with Korean features and tastes. Others see K-pop as a foreign spectacle, and still wish to belong to the traditional, “all-American” masculinity. Moreover, the lifestyle and displayed wealth of these pop stars (the excessive grandiosity in K-pop videos can be unsettling) adds the dimension of class barriers into the already complex intersection of ethnicity, sexuality, and nationality.

Emerging from historical legal barriers to interracial relationships and emasculating media narratives, Asian-American men in the 21st-century are coming to an awareness and protest of their devalued masculinity. Like tectonic plates, the morphing landscapes of YouTube, social gender roles, and international popular culture consumption send quakes under the feet of Asian-American identity, fissuring past tradition. Navigating and negotiating sexual identity, collectively and individually, Asian-American men must understand and discuss, as Judith Butler put it, the hegemonic social conventions and ideologies scripting our most personal acts. With that awareness, the road toward self-creation and identification opens wider, freer.

Originally published at The Wang Post.

— — —

Works Cited

Fung, Richard. “Looking For My Penis,” (1991). In Bad Object-choices (Eds). How Do I Look? Queer Film & Video, pp. 145-168. Seattle: Bay Press. http://www.richardfung.ca/index.php?/articles/looking-for-my-penis-1991/

Han, Chong-suk. “Being An Oriental, I Could Never Be Completely A Man: Gay Asian Men and the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Class,” (2006). Race, Gender, and Class: Volume 13, No 3-4. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675174

Maliangkay, Roald. “The effeminacy of male beauty in Korea,” (2010). The Newsletter, No. 5. http://www.iias.nl/sites/default/files/IIAS_NL55_0607.pdf

Park, Michael. “Asian American Masculinity Eclipsed: A Legal and Historical Perspective of Emasculation Through U.S. Immigration Practices.” The Modern American 8, no. 1 (2013). http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1164&context=tma

Pasztory, Esther. “Paradigm Shifts in the Western View of Exotic Arts.” http://www.columbia.edu/cu/arthistory/courses/Multiple-Modernities/essay.html

Shiau and Chen. “When Sissy Boys Become Mainstream: Narrating Asian Feminized Masculinities in the Global Age” (2009). International Journal of Social Inquiry, Vol. 2, pp. 55-74. http://www.socialinquiry.org/articles/mak-esas-4.pdf